The Thrills and Spills of Researching the Distant past

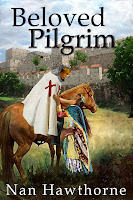

Nan Hawthorne, author of Beloved Pilgrim, a novel of the Crusade of 1101

In history class in college we learn about the difference between primary and secondary sources, but anyone who has tried to research events in the Middle Ages knows that primary and authoritative are not necessarily one and the same. The Crusade of 1101 stands out as one example. Of the three so-called primary sources for chronicles of this time and event, only one, Anna Comnena’s “The Alexiad”, is truly primary, the others by Exxehard, Abbot of Aura, and Albert of Aix being respectively written by someone who did not travel with the three arms of the crusaders in Turkey and by someone who was never there at all but writing ten years later. Even Anna’s is by someone present for only those events that took place in Constantinople at her emperor father’s court. How then can one be certain what she reads bears any resemblance to the historical facts?

Many historical novelists, Sharon Kay Penman, for instance, do intensive research by traveling to locations where their stories take place and finding those primary sources in court records and monastery libraries. The amount of this sort of material is surprising and a testament to the packrat mentality of the record keepers themselves. However, even where an individual author can lay hands on this sort of primary source, not every event was written about or can one find the records still in existence. This is very much the case of the Crusade of 1101 and many other events of the early Middle Ages.

My own research on the Crusade of 1101 for my novel “Beloved Pilgrim” started with the work of historian Sir Steven Runciman. His highly regarded “A History of the Crusades” (three volumes, Cambridge University Press 1951) is admittedly secondary and based entirely on materials such as the chronicles mentioned above. What you have with Runciman is a combination of masterful research and analysis. He clearly compiled his information painstakingly and made a coherent narrative from it. However, even I as a lowly historical novelist with my research buddy, a medieval warfare enthusiast, found some unlikely conclusions based on knowledge of the fighting techniques of the era and the terrain and nature of the land where the battles occurred. How does this reflect on the rest of his research?

Whether an author is a strict historian or a novelist aiming to turn historical events and characters into enlightening entertainment, it is important to think outside the box of the chronicles of the era. The fact is that monastic clerks kept most records on the events. They could certainly be relied upon to keep track of certain economic and legal information, but when recounting events let’s just say their bias was showing. It is the contrast with narratives by Islamic scholars this is made most clear. These latter tended to present factual detail while the monks were the “spin doctors” of their culture. For example, while the Christian chronicles make little or no reference to women who were involved in the Crusades and in particular in battle, the Islamic scholars had no compunction about describing the bodies of female combatants after a battle, such as the siege of Acre.

The researcher can derive some insight into the personalities involved in such an event by what people involved in what happened are willing to say about it. That occurred to me with the very fact that the leaders of the Crusade of 1101 who acted in what seems to my mind to be a desperately dishonorable desertion of their followers nevertheless admitted to what they had done. What sort of people would expect admiration and approval for cowardice of this magnitude? Luckily, being a novelist, I was in a position to use this in the characterization of these historical figures. I was able to show them behaving badly, whereas a historian would balk at such storytelling.

My conclusion about doing research on the Crusade of 1101 was that I needed to do four things:

- Read the generally accepted accounts,

- Consider what I read against other sources,

- Apply my own judgment and common sense, and

- Remember that I am a storyteller and not writing a history textbook.

The historical novelist has a responsibility to her readers not to stray egregiously from the known facts of an event or historical person, but when the “known facts” are in question, are secondhand and may even consist of propaganda, it is necessary to come clean to readers about any embroidery on the facts as they are known and to stay faithful to what one has learned, not imagined, about the life and culture of the periods she depicts in her novels.

Nan Hawthorne’s recently released “Beloved Pilgrim”, the story of a young woman who chooses to live and fight as a man in the doomed Crusade of 1101, is available at Amazon and Smashwords.

![]() Tweet This Post

Tweet This Post